IEN Europe: Could you please describe the main characteristics of your new sensor and give a general description of the production process to our readers?

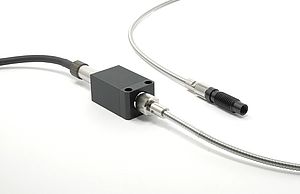

Dr. Malte Köhler: The sensor is small (e.g. 1 µm edge length or even less, which is likely the smallest sensor in the world) and can solve manifold problems. One is that conventional sensors typically come with requirements that might hinder or even prohibit the integration like sensor size, thermal reaction time for temperature sensors or creeping effects for strain gauges with unmatched material parameters. Our technology has low requirements as the sensor is additively manufactured and directly printed to the surface. This means that the integration of our sensors will (in most cases) not hinder the original use case of the product: Hence we call our technology malleable.

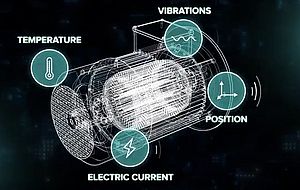

We can produce two different types of sensors:

Temperature: We can measure absolute temperatures, heat fluxes and even temperature fields (with sensor arrays).

Forces: Our sensor is strain sensitive and reacts naturally to mechanical loadings of the substrate. By carefully deciding on the sensor position on the part and potentially redefining the geometrical configuration of the part (minor geometrical adjustments that do not reduce the part’s mechanical stability) virtually all forces can be measured. For robots we can measure normal and tangential forces (with respect to the surface), we can measure torque, compressive and tensile forces and with a small MEMS chip even absolute pressures.)

The production process is fully automated and features quality control as well as traceability per sensor (or per part). It involves three process steps:

- Surface Preparation with thin film electrodes: Thin film electrodes are applied to the surface. Here we use standard processes found in the industry like PVD (physical vapor deposition), sputtering etc. The electrodes are defined in their geometrical configuration by means of microstamping/micro imprint, lithography or by means or direct structuring methods (e.g. laser ablation).

- Fabrication of our Sensor: With the electrodes in place, digid applies its nanosensor. This is a lithography process that provides a sensor element. The specific process is a trade secret. However, the process does not alter the substrate and can be even applied on polymers. Established materials are: Metals, Ceramics, Glass, Polymers and Semiconductor materials.

- Contacting the sensor with wires: The sensor now sitting in between the electrodes and be wired with the following processes: wire bonding, pogo pins, ultra sonic wire welding, soldering or gluing (conductive epoxy). The method for contacting must not be precise as the base resistance of the sensor can be tuned to high values (Megaohms).

The production process is patented and industrialized so that mass production is available to our customers.

The Nanosensors are developed under the medical device QMS ISO 13485 and can be also used in medical products after certification. At the same time not every product digid is developing is a medical product. The nanosensors can be applied also outside the norms of ISO 13485.

IEN Europe: What are the main application fields at the moment? Which industrial applications could benefit from integrating your sensors and is there an inherent technical limit?

Dr. Malte Köhler: We have customers in automotive, medical and the preventive maintenance (aerospace) industries at the moment.

Virtually no technical limits exist, since the sensor is usually smaller than the device. For too large applications we usually use sub-assemblies as this increases production speed. The size limit for the sensor usually arises from the structuring method used to fabricate the two separated electrodes and not from the sensor printing itself. We can use lithography or stepper lithography as well as laser structuring, micro imprint or nano imprint lithography for complex substate geometries. Our sensor is ultra-localized (e.g. for force measurements) and relies on homogenous materials (that are typically used for force sensing applications).

We cannot produce our sensors on liquid or gel-like materials. So, the sensor always requires a substrate.

IEN Europe: From the perspective of a potential user: How could a company integrate such a small component, and which interfaces would be used?

Dr. Malte Köhler: We always recommend our customers to print the sensor directly on the surface of their product, or on a suitable subassembly. This circumvents possible problems arising from packaging, like the need for glueing the sensor on the product as this in cooperates additional materials with different material properties like thermal expansion coefficients. The subassembly can be welded or clamped to keep the matched material properties. In addition, the directly printed sensor features best coupling to the surface and therefore minimizes thermal reaction time or mechanical dampening. In either way, the printed or glued sensor is contacted via thin film electrodes or bond wires and can be measured with readout electronics featuring an electrical resistance or voltage measurement.

IEN Europe: Can you see any possibility of making the sensor units even smaller in the near future, and to what extent?

Dr. Malte Köhler: Yes, we can certainly go smaller than the current sensors with 1 µm edge length. The way to go is to use more advanced structuring methods (nano-imprint-lithography or stepper lithography) for electrode definition which are currently more expensive than regular technologies (UV lithography, laser structuring). However, all these structuring methods are industrially approved, mature and readily available to use. If we see the need we can easily switch. The lowest we think we can go is so several 10th of nanometers.

IEN Europe: Thank you for sharing these interesting insights with us.